Business management theory and research on entrepreneurship can be powerful tools for arts and culture organisations. A UK creative studio and social enterprise believes arts organisations should employ more economists and management scientists.

What is the purpose of an arts and culture organisation? The obvious answer is: to make art. However, many of us in the sector also care about the effect of the art and might consider the purpose to be: to positively impact people with art. Whatever your answer, I’m guessing it’s unlikely you thought it was to make money.

A profit-making business, meanwhile, has a clear purpose. Many new businesses, such as B-corporations, are adopting a stance of also doing good, but none of them would make doing good subservient to making money. Business management doctrine has been that it’s the duty of managers to maximise value for shareholders. Because of this, great efforts are taken to ensure the interests of management and shareholders are aligned – such as by including shares in the remuneration package. Given the dominant form of cultural organisations is non-profit, what are our purpose and goals from a business management perspective? Managers do not own shares

in nonprofits, and asset locks mean (quite rightly) that profits cannot be distributed. So how can theories of maximising shareholder value apply to innovation and social impact in arts and culture?

Budgets target a tiny surplus, leaving little room for future investment in innovation and resulting in a negative feedback loop of underinvestment in new models, new technologies and new processes

No matter our purpose and our goals, we need to invest time and money up front in reaching them. Time and again, in my research for my MSc in business innovation and in Social Convention’s work with arts organisations on the ground, a lack of investment is cited as a major barrier to growth, impact and innovation. However, many people we have worked with and many of the subjects I interviewed for my research see profitability as a zero-sum game, where profit-making is inherently detrimental to impact. Budgets and plans target a tiny surplus, leaving little room for future investment in innovation and resulting in a negative feedback loop of underinvestment in new models, new technologies and new processes. Yet these are the very things that can help deliver more impact in the long run and/or can be reinvested in more art and culture. For example, innovating to improve accessibility was a key motivator among participants in my research, but financing it was the most commonly cited barrier.

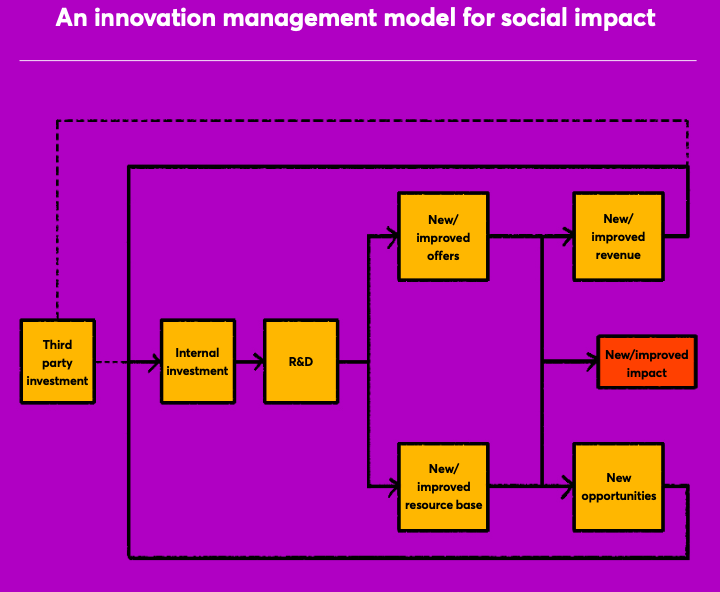

If we are to unlock a wider range of capital and investment sources – including social impact finance – for cultural organisations, we need to think more seriously about business, management and profitability. In a for-profit business, the role of management is to design strategy and implement business plans that deliver profit. Innovation and management theory come together in the concept of sustainable competitive advantage. This is the set of resources, assets and capabilities (the resource base) that allows an organisation to deliver the plans, products and processes that deliver the profit.

Without competitive advantage, alternative offers – substitute products, services and experiences – will capture too many of the customers in a given market for you to survive (break even), let alone thrive (turn a re-investable profit). Sustainable competitive advantage comes from the ability to adapt to the changing world in which the organisation operates. This requires innovation, which in turn requires the adaptation of the resource base, which, as we’ve noted, costs time and money.

For arts and culture, competition used to be largely confined to the local marketplace. But digital offers are rapidly exposing the sector to competition in a global content and experience ecosystem. This new ecosystem of experience providers and content makers has a huge resource base and is investing constantly in its own competitive advantage. To compete, arts and culture organisations need to generate more surplus so that they can either re-invest directly in R&D and adapt their resource base to the changing operating context or secure third-party capital to invest in said innovation – or, in all likelihood, both.

How we measure success will drive how we manage our organisations and how we operate within the ecosystems we are part of. The great thing about social impact finance is that it encourages a dual focus on both social and financial measures. Rather than seeing management as an act of balancing two countervailing forces, we can see it as the creation of positive feedback loops that achieve both the social and financial goals. Barely surviving by breaking even will result in diminishing returns over time, leading to insolvency and closure unless management can reduce costs faster than the diminishing returns (usually through automation or downsizing, which will likely have a negative social impact). My research found that arts and culture organisations are already intensifying workloads on staff in order to cope with the opportunities and threats afforded by digital technologies, because innovations to achieve the necessary positive feedback loops have not yet diffused through the ecosystem. However, they do exist. Various new models for digital touring of theatre works are emerging, creating new access points for audiences and new opportunities for artists.

A common response to the need to innovate in order to remain competitive is to work with external partners in a project-oriented manner. This makes sense in organisations where it’s the norm to employ significant numbers of freelancers for each new show or exhibition, and also in the context of capital scarcity. However, while it can be a very helpful early-stage approach to R&D, in the medium to long term it leaves important parts of the required resource base outside the organisation. New skills and capabilities are not properly captured and internalised, which results in higher long-term costs and/ or new opportunities unrealised. Sometimes it’s helpful to hire what we need when we are unsure of how long we will need it or we aren’t confident in our ability to scope our requirements. However, in the long run, short-term hiring is usually more costly and the asset is owned by someone else – an asset that might be able to be leveraged not only for the project at hand but for other/future opportunities. An important skill for organisations is to know how and when to internalise new capabilities and resources.

This takes us back to the need to increase our ability to generate surplus to cope with the capital intensity of innovation and to secure finance from third parties to fund it. Free cash flow is the engine of growth. Without it, we can’t invest in the long term, but instead are stuck in short-term cycles of cash flow management. At Social Convention, we’ve seen our own and our collaborators’ growth and impact opportunities accelerate once we’ve created a model that generates surplus cash and generates impact. This is a win-win mindset – but it’s not only a mindset. Rather, it is underpinned by rigorous theory and can be achieved through defined practical approaches. Risk can never be removed, and success can never be guaranteed, but thinking like an investor – or like the CEO of a publicly listed company – could help us all make more art and do more good.

Social Convention is an innovation agency and culture lab supporting the development of new arts and culture through access to space, skills and technology for creative entrepreneurship. We use our resources and our networks to help create sustainable new work through new business models and new audience relationships.

Bibliography and further reading

- Arend, R.J. and Bromiley, P., ‘Assessing the dynamic capabilities view: Spare change, everyone?’, Strategic Organisation 7(1) (2009), 75-90

- Bakhshi, H. and Throsby, D., ‘New technologies in cultural institutions: Theory, evidence and policy implications’, International Journal of Cultural Policy 18(2) (2012), 205-222

- Bakker, G., ‘Sunk costs and the dynamics of creative industries’ in ) The Oxford Handbook of the Creative and Cultural Industries, ed. by C. Jones, M. Lorenzen and J. Sapsed, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015) pp.351-386

- Bolton, M., Cooper, C., Antrobus, C., Ludlow, J., and Tebbutt, H., ‘Capital Matters: How to build financial resilience in the UK’s arts and cultural sector’. (London: Mission Models Money, 2010)

- Brooks, A.C., ‘Toward a demand-side cure for cost disease in the performing arts’, Journal of Economic Issues, 31(1) (1997), 197-208

- Crealey, M., ‘Applying new product development models to the performing arts: Strategies for managing risk’ International Journal of Arts Management, 5(3) (2003), 24-33

- Helfat, C.E., Finkelstein, S., Mitchell, W., Peteraf, M., Singh, H., Teece, D. and Winter, S.G., Dynamic capabilities: Understanding strategic change in organizations (John Wiley & Sons, 2009)

- Hesmondhalgh, D., The Cultural Industries (3rd ed.) (London: SAGE, 2009)

- Labaronne, L. and Tröndle, M., ‘Managing and evaluating the performing arts: Value creation through resource transformation’, The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 51(1) (2021), 3-18

- Noori, J., Tidd, J. and Arasti, M.R., ‘Dynamic capability and diversification’ in From Knowledge Management to Strategic Competence: Assessing Technological, Market and Organisational Innovation. Series on Technology Management, 19(3) (2012)

- Reidy B. K., Schutt, B., Abramson, D., Durski, A., Ellis, E., Casale, L and Throsby, D., Understanding the Impact of Digital Developments in Theatre on Audiences, Production and Distribution, Arts Council England and UK Theatre, London (2016)

- Voss, Z.G. and Voss, G.B., ‘Exploring the impact of organizational values and strategic orientation on performance in not-for-profit professional theatre’, International Journal of Arts Management, 3 (1) (2000), 62-76